More Thoughts on Polarization

Or, why quantifiying abstractions is pretty difficult.

It is often taken as common knowledge by scholars, pundits, and journalists that the United States now exists in a period of intense “polarization”. The United States is a country divided along political lines—be they partisan, ideological, or geographic. This essay is challenges the assumptions on which these positive claims rest as well as the normative prescriptions which so often follow. Above all, competent research on and characterization of polarization requires precision in language and concept. The population of interest (most often the mass public or elites), the level of analysis, and the substantive content of your quantity of interest must be clearly defined and not over-generalized. Finally, polarization of any kind must be understood as a dynamic process, not simply as a synonym for “division”, “sorting”, or “animosity”. I close by urging the reader to center the substantive, material outcomes of political programs and to be skeptical of characterizations of polarization as a primary political concern.

Academic discussions of partisan polarization typically focus on one of two populations:

- The mass public.

- Elites (most often members of congress).

and one of two quantities of interest:

- Democrats’ and Republicans’ ideological positions (ideological polarization).

- Democrat and Republican dispostion towards one another (affective polarization).

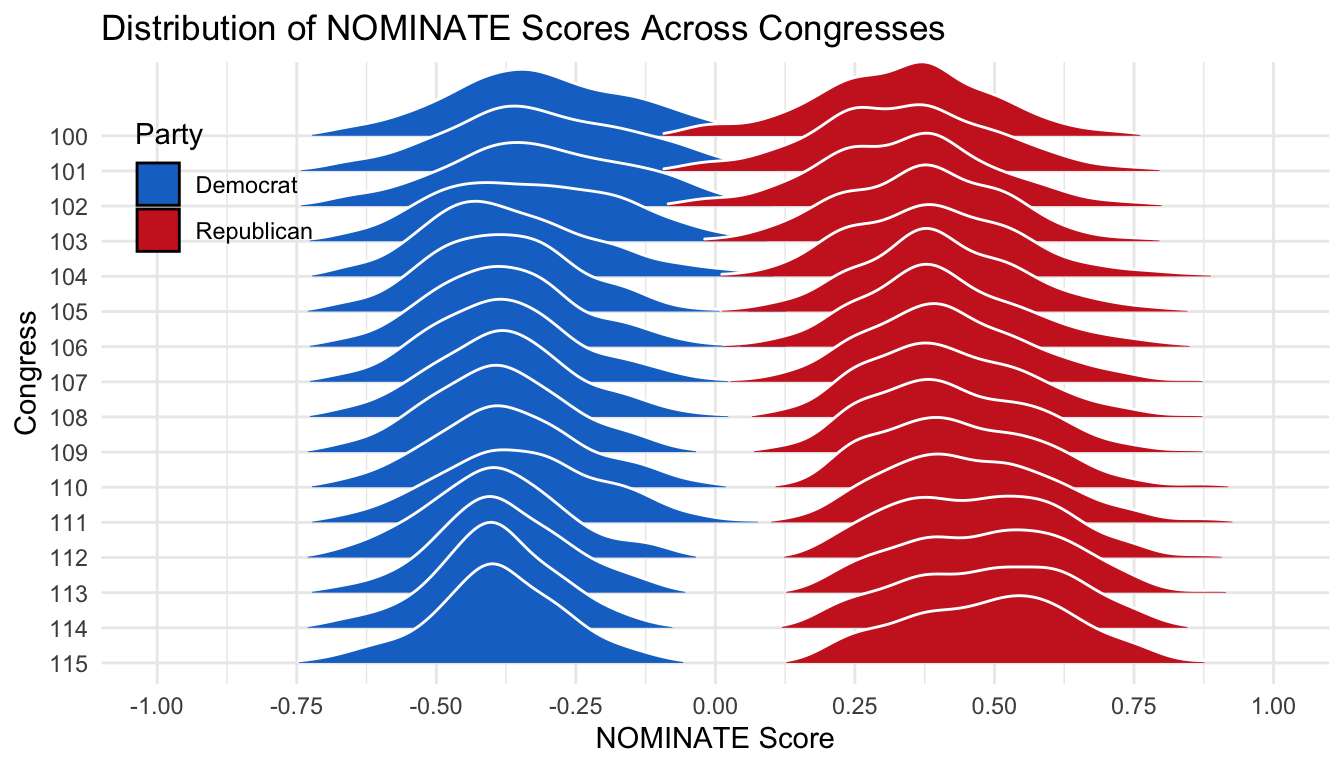

Typically, elite polarization research focuses on ideological positions of politicians—often measured through the conceptually problematic NOMINATE score (Poole and Rosenthal 1985). Not only do NOMINATE measures not account for the content of a bill being voted on beyond its subject area, the NOMINATE score of party \(D\) are necessarily dependent on the positions of party \(R\), and vice-versa.

Consider the 103rd and 104th congresses. Republicans ran in 1994 under the promise of Newt Gingrich’s unabashedly rightwing legislative agenda, as described in the “Contract With America”. The new Republican majority put forth a swath of proposals further right than those of their predecessors. Using NOMINATE, there is no way to differentiate between a rightward shift in Republicans and a leftward shift in Democrats. If the Democrats’ ideologies stayed constant from the 103rd to 104th congress, we would still expect a “left” shift in their NOMINATE scores (which we in fact see in Fig. 1), as any one Democrat would be less likely to vote with the increasingly extreme Republicans. For a party to maintain a stable distribution of NOMINATE scores in the face of an increasingly extreme opposition their preferences would have to shift towards the other party, to continue voting with them at a comparable rate. NOMINATE is a useful tool for describing partisan sorting (increasing homogeneity of political preferences), but says nothing of ideological extremity.

A better measure of ideology could treat a party or representative’s position at \(t_0\) as a base category, defining that subject’s ideology at \(t_1\) in terms of the number of issue areas on which (or the degree to which) the subject shifted left, right, or not at all. As with NOMINATE, such a measure would include an arbitrary starting point, but would improve on NOMINATE by making that point clearly defined, conceptually relevant, and independent of other actors at any one time. An ideological shift in either party could be clearly discerned, a shift in one party would have no bearing on the position of the other party. Finally, while defining an objective ideology is difficult, categorizing shifts as being to the left or right is relatively easy. Whatever imperfect measurement is used, in the absence of an objective measure of ideology researchers should not shy from building qualitative arguments.

Despite NOMINATE’s lack of content validity, there is broad agreement among scholars that elites have polarized along ideological lines; that is Republicans have become more reliably conservative and Democrats’ more liberal. As shown in the distribution of NOMINATE scores from the 100th to 115th congresses below, even under the strong assumption that NOMINATE is a valid measure of ideology1, characterizations of elite polarization as relatively symmetrical across parties are somewhat misleading.

While there has been slight leftward movement among Democrats (mostly from the 100th to 104th congresses), the rightward drift of the Republican party is much more pronounced. When the distance between distributions of partisan ideology is highlighted by researchers—rather than the location and scale of each distribution—the data generating process is obscured. Relatively equal movement in both parties is implicit in the word “polarization”. This may seem a small, perhaps pedantic nitpick. Not so! Not only does “polarization” warp researchers’ perception of the descriptive contours of the data, the misapplication of terms propagates to the more widely consumed venues through think-tanks pundits, and news media.

Scholarly and popular accounts of elite polarization take polarization as extant, to be the “fault” of both parties, and as ex ante detrimental to quality representation. This chain of misperceptions, predicated on faulty assumptions about NOMINATE scores and mass ideology has created a bevy of authors decrying a “disconnect” between moderate constituents and their extreme representatives (Fiorina and Abrams 2012) or similarly, “leapfrog representation”, whereby the sensible, moderate public is forced to choose between two equally unappealing, ideologically extreme parties (Bafumi and Herron 2010).

These authors point to the extensive body of public opinion research assuring political scientists that the public is not composed of ideologues Zaller et al. (1992), while noting that congress is increasingly dominated by ideologues. The central flaw in this argument is the conflation of two distinct states: “lacking an ideology” and “being a moderate”. When authors write about leapfrog representation or the “exhausted center” 2 they leverage evidence that voters have relatively few issue positions congruent with the party that represents them to argue that most members of the public are, in fact, moderate.

The portrayal of apparent moderate voters as holding moderate preferences is erroneous. To the extent that members of the public hold preferences they are unconstrained; taking leftwing positions on some issues, rightwing positions on others, as do moderates b and c in the table below D. Ahler and Broockman (2015)3. This variation is flattened, because an individual’s ideology is almost always measured in one of two ways:

- A self report with little predictive validity.

- An average of reported issue positions, scaled or otherwise.

As identified by (D. J. Ahler and Broockman 2018) and illustrated below, an ostensibly moderate ideology does not imply moderate policy positions. All of the hypothetical voters appear to be perfect moderates, yet agree on no single issue. In contrast, moderates as they manifest in the elite—e.g. New Labour in the UK and the Third Way Democrats in the U.S.— are themselves ideologues; possessing highly constrained sets of moderate preferences (more akin to the “Moderate a” in the table). Ideology is not predicated on extremity.

| Issue | Moderate a | “Moderate” b | “Moderate” c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion | .5 | 0 | 1 |

| Gun Control | .5 | 0 | 1 |

| Climate | .5 | 0 | 1 |

| Deficit | .5 | 0 | 1 |

| Free Trade | .5 | 0 | 1 |

| Health Care | .5 | 1 | 0 |

| NATO | .5 | 1 | 0 |

| Green New Deal | .5 | 1 | 0 |

| UBI | .5 | 1 | 0 |

| Police Defunding | .5 | 1 | 0 |

| MEAN: | .5 | .5 | .5 |

As citizens’ average ideologies are bereft of substance and as citizens’ themselves largely lack the ability to match substantive issue positions with relevant ideological labels Zaller et al. (1992), the assertion that elite ideological polarization is a grave threat to quality representation is not only unfounded, but Ahler and Broockman argue that interventions to decrease elite polarization and encourage moderation on a policy-by-policy basis stand themselves to decrease the quality of representation.

This frankly relieving fact has not stopped the growth of a cottage industry of anti-polarization books, op-eds, and think-tanks from urging such interventions against ideological and affective polarization (though the distinction is not always made clear) among elites and the public. A quick search for books about “political polarization” yields 557 results on Amazon.com, written by journalists, political scientists, politicians, and marriage counselors, sporting titles like: Dead Center: How Political Polarization Divided America and What We Can Do About It4, Them: Why We Hate Each Other—and How to Heal5, and I Love You, but I Hate Your Politics 6.

Works in this budding tradition frequently contain a haphazard mix of evidence of mass ideological and affective polarization; not always careful to distinguish between the two. For example, Morris Fiorina’s Culture War? argues that Republicans and Democrats at the mass level aren’t actually hostile towards one another because their preferences are unconstrained (Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope 2005), while Alan Abramowitz’s The Disappearing Center cites increasing political engagement as evidence of increasingly extreme mass ideology (Abramowitz 2010). To be clear, partisan animosity has been steadily increasing since the 1980s Klar, Krupnikov, and Ryan (2018) but whether this disdain should be characterized as polarization is dubious (Klar, Krupnikov, and Ryan 2018). In any case, social trends are no excuse for poorly defined concepts found in these works.

The praise heaped on Vox editor Ezra Klein’s recent book Why We’re Polarized is illustrative of more general, normative concerns about the way polarization is discussed. Francis Fukuyama, of The End of History fame, calls polarization

“…the most central of political puzzles…”,

MSNBC host Chris Hayes says

“[polarization] just might be our central, perhaps fatal problem…[the book is] absolutely critical in our current moment”,

and moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt writes:

“Something has gone terribly wrong with American politics in the last decade or so”.

All of these statements take polarization (it is not clear if by “polarization” they mean ideological, affective, etc) as de facto harmful; something to be fixed, a state from which the country must “heal”.

This same rhetorical thread is the foundational principle of groups like More in Common, which “works on both short and longer term initiatives to address the underlying drivers of fracturing and polarization, and build more united, resilient and inclusive societies.” building a resilient and inclusive society is, to be sure, a worthwhile normative goal; but again “division” is centered as the principal societal ill to be corrected. Just as NOMINATE scores erase substantive distinctions between legislators, policy, and party; the ink spilled fretting over polarization flattens political discourse. In a polarization-centric paradigm, policies and politicians are praised or condemned by way of their interaction with polarization, not for their substantive content. One driving force behind congressional sorting from the 1940s to 1990s is the decline, party switching, retirement, and death of the pro-segregation Southern Democrats, who often voted with Republicans on race and social issues. I find it hard to believe that our political culture would be healthier if both major parties contained a caucus of unabashed racists7. This may seem a ridiculous point, but it illustrates the obvious: that the importance of considering a politician or policy’s divisiveness should be second to its substance.

Ironically, reducing politics to a meta-critique of political discussion centered around “polarization”, “partisanship”, or “tribalism” makes consensus building—depolarization—all the more difficult; ensuring that discussions of how best to apply the State’s monopoly on violence are inseparable from concepts of party and tribe. Would it not be more effective to intervene against polarization by building an affirmative case for a political program? Just because something is divisive at \(t_1\) does not mean it is undesirable, nor that it will continue to be divisive at \(t_2\). The public’s opinions are malleable, and political elites have the power to shift them (Lenz 2013). Rather than simultaneously scolding citizens who are politically disengaged8 and pearl clutching when they’re too engaged, elites should focus on advocating for their own positive vision of the State.

Whatever small proportion of political science work reaches the public or gains influence outside the discipline is often filtered through journalism and punditry. As a consequence, political scientists have a responsibility to monitor how insights from our discipline are applied outside of academia. In some cases, the same researchers describing polarization in journals are warning about polarization in bestselling books, or the pages of The Washington Post. Flimsy assumptions and misguided interventions are flimsy and misguided whether published in the APSR or the New York Times. Political scientists should take care not to overgeneralize, avoid conflating partisanship with ideology, and avoid treating polarization itself as a disease.

Some Disorganized Closing Thoughts to Prompt Discussion:

Appeals to process and norms box the actor making the appeal into a corner. Liberals should not say that the court has gotten too ideological, they should make the case that the courts are being used for nefarious ends. They should want to appoint ideological judges, just that those judges should have a good ideology (“good” is of course, fairly subjective) and should make the case for each as such.

In a situation where one set of political actors act (correctly) as though politics is a contest over a monopoly on state violence, and is highly motivated to secure their hold on that monopoly while an opposing set of actors is committed to fairness and compromise the first set of actors will get more of what they want, because the second is both reactive in its program and conservative in its prescriptions.

“Extreme” \(\neq\) “Wrong”9

“moderate” \(\neq\) “right” | “reasonable” | “sensible”10

There are certainly negative outcomes associated with socio-political division, but commentators, politicians, and researchers should take care not to assume that the division is the cause of the problem. When political decisions threaten your safety, health, or livelihood, it is not unreasonable to be upset with those who have made the decisions.

References

As opposed to what NOMINATE really is, a measure of sorting.↩︎

Zaller analogizes survey response as akin to drawing a range of positions from a hat (Zaller et al. 1992)↩︎

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38714379-them?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=g6ych9rby0&rank=1↩︎

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/41150276-i-love-you-but-i-hate-your-politics?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=IzxOufQk7g&rank=1 (this is the one by a marriage counselor)↩︎

To be fair, I doubt many anti-polarization pundits are arguing for exactly this↩︎

I for one am very excited to see which demographics didn’t turn out in this election.↩︎

Obviously, a position could be both “extreme” and “wrong”, but extremity is not a sufficient condition for wrongness.↩︎

See above.↩︎